Ukraine, China’s spy balloons, divisive US politics fueled by the media (not just social), the far-right loonies and liars, the odd economy with low unemployment, inflation starting to come down, fear of recession abating, but public perception not changing—proof of our absurd world. All that aside, CLIMATE CHANGE is our number one threat. An existential issue for both the structures of society and our individual purpose and values.

PS: Unless you love words or digging into concepts you might want to skip this blog. I love both, so I got carried away.

The term “existential threat” gets thrown around regularly, but what, exactly, does it mean? I have to admit that my first 2 years of college I was an unhappy, “misplaced” student, who resorted to a comfy corner library chair reading the French existentialists (albeit in translations) instead of going to class. Thus when I first heard of an existential threat, I thought: “I get this!” But there’s more to this than meets my memory.

There are actually a few ways of defining the semantics of existential threat; but let’s forget “threat” for a minute. Existentialism is actually quite a kettle of thought and expression with an interesting history.

The Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) is considered by many as the “father” of existentialist thought. He was many other things too, which complicate his specific contributions. Primarily it was his view of the individual as a solitary being with free will and the anxiety that produced, and the world as absurd that led to existentialist development. The word, itself, although based on Kierkegaard’s writings, wasn’t introduced until 1945 when the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel used it (L’existentialisme ) to describe Jean-Paul Sartre, who initially rejected it, then took it to describe his work.

Many philosophers contributed to the concept, thus, its many facets. Contributors included Georg Frederik Hegel (1770–1831). Who “postulated a form of absolute idealism by including both subjective life and the objective cultural practices on which subjective life depended within the dynamics of the development of the self-consciousness and self-actualisation of God, the Absolute Spirit. Despite this seemingly dominant theological theme, Hegel was still seen by many as an important precursor of other more characteristically secular strands of modern thought such as existentialism and Marxist materialism. Existentialists were thought of as taking the idea of the finitude and historical and cultural dependence of individual subjects from Hegel, and as leaving out all pretensions to the Absolute.”[i] [For my purposes, I’m ignoring the abstracted path to Marxism.] Other contributors included later German philosophers Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers; and Spanish philosophers José Ortega y Gasset and Miguel de Unamuno. It was the French who popularized the concepts: Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, in particular.

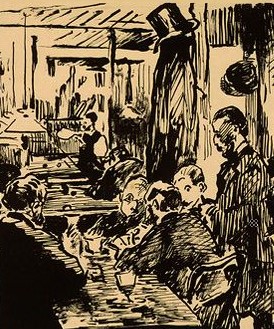

Authors, artists, and filmmakers all drew on concepts of existentialism in their work, thus adding more interpretations available to a wider audience. “Beyond the plays, short stories, and novels by French luminaries like Sartre, Beauvoir, and Camus, there were Parisian writers such as Jean Genet and André Gide, the Russian novelists Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky, the work of Norwegian authors such as Henrik Ibsen and Knut Hamsun, and the German-language iconoclasts Franz Kafka and Rainer Maria Rilke. The movement even found expression across the pond in the work of the ‘lost generation’ of American writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, mid-century ‘beat’ authors like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsburg, and William S. Burroughs. Its ideas are captured in films by Ingmar Bergman, Michelangelo Antonioni, Jean-Luc Goddard, Akira Kurosawa, and Terrence Malick. Its moods are expressed in the paintings of Edvard Munch, Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso, Paul Cézanne, and Edward Hopper and in the vitiated forms of the sculptor Alberto Giocometti. Its emphasis on freedom and the struggle for self-creation informed the radical and emancipatory politics of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X as well as the writings of Black intellectuals such as Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, and W.E.B. Du Bois. Its engagement with the relationship between faith and freedom and the incomprehensibility of God shaped theological debates through the lectures and writings of Karl Barth, Paul Tillich, and Martin Buber, among others. And, with its penetrating analyses of anxiety and the importance of self-realization, the movement has had a profound impact in the development of humanistic and existential approaches to psychotherapy in the work of a wide range of theorists, including R.D. Laing, Rollo May, Viktor Frankl, and Irvin Yalom.”[ii]

As with the Marxist path, I am discarding the religious path for the purposes of this discussion. While legitimate philosophies, I find both Marxism and religious existentialism, thought bent for specific ends. I can picture it as an early muscular Russian Marxist bending a bar of steel and a berobed white-haired, bearded religious convert pounding nails into 2 pieces of wood to form a cross, thus emasculating existentialism to their specific use for large groups of people, not individuals.

It’s helpful to remember the historical environment of existentialist development. It became popular after World War II, with its Holocaust, which seemed even more horrible as we learned of the systematic mechanization of terminating the “unwanted” from Jews, to Roma, to the physically and mentally handicapped (there were genocides before-and after-that, but this was the first we saw on screens in theaters and early TV), the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the continued existing possibility of such wide-spread destruction.

WOW. No wonder no one can define it succinctly. But I will try to present it in layperson’s terms as it relates specifically to the “existential threat of climate change.” What makes it a threat is, in a sense, part of such a definition. Existentialism views the human individual as just that, a single entity with free will, but because we have free will, we also have responsibility resulting in our individual struggle to make sense of a complex, ever-changing, absurd world. This combination results in anxiety, feelings of meaninglessness, nihilism, detachment, yet at the same time we are constantly forming ourselves by our choices and our “being” in this world.

As negative and difficult as that may sound, existentialism isn’t morally bankrupt. Given that we have free will, we have a choice to acknowledge that and live our lives responsibly and in ways that allow others to do the same.

In terms of climate change, it’s clear we have caused it both individually and organizationally from nation states to corporations to the global financial marketplace. From the aspect of existentialism, how we perceive our reality is critical. In one sense, it denies dualism (us/them, human/the Earth, mind/body) and a totally scientific-technological solution. We are part of the natural world, as much an individual, as a being connected to all else, albeit an individual that can only make choices for ourselves.

Whether you consider yourself an existentialist or not, for our species and so many others to survive, it’s up to each one of us to make wiser choices.