In my last blog under a photo of a modern sculpture in Crete, I promised to write about that. But first a story from ancient Crete. This is taken from my book, Voice of a Voyage: Rediscovering the World During a Ten-year Circumnavigation , Chapter 11, The Eastern Mediterranean: Thousand-page Stories, the section entitled “Eastern Greece: Identity Through Memory.”

Our first stop in Crete was the Lychnostatis open-air museum, where I found the epigraph for this chapter [it is included in the previous blog]. This museum gave us a view of the everyday life in central Crete over time. We enjoyed all of Crete, especially the museums, large and small. Of special interest to us was our visit to Knossos and delving into the Minoan world and to Gortyn, the site of the oldest (and the longest) legal inscription in the Western world.

A scene from the site of the Minoan city of Knossos in Crete.

A scene from the site of the Minoan city of Knossos in Crete.

What struck me most in Knossos was not only the age of what I was seeing, but the color, and the perception that I could actually see life there in the golden age of the Minoans. Knossos was first inhabited in 7000 BCE, the Neolithic period. The cradle of Western civilization via the Minoan culture started about 3500 to 3000 BCE, but came into its own from about 1950 BCE to 1400 BCE, surviving two major natural catastrophes: an extremely earth-shattering earthquake and a monster tsunami in 1730 BCE and 1570 BCE respectively. Before that, there seemed to be a five hundred-year time of peace, a time before people learned to hate each other’s religions. Cretans worshipped a mother-goddess, and the Mycenaeans on the Greek mainland were patriarchal, yet they coexisted without wanting to take over the other, or, worse, to convert them.

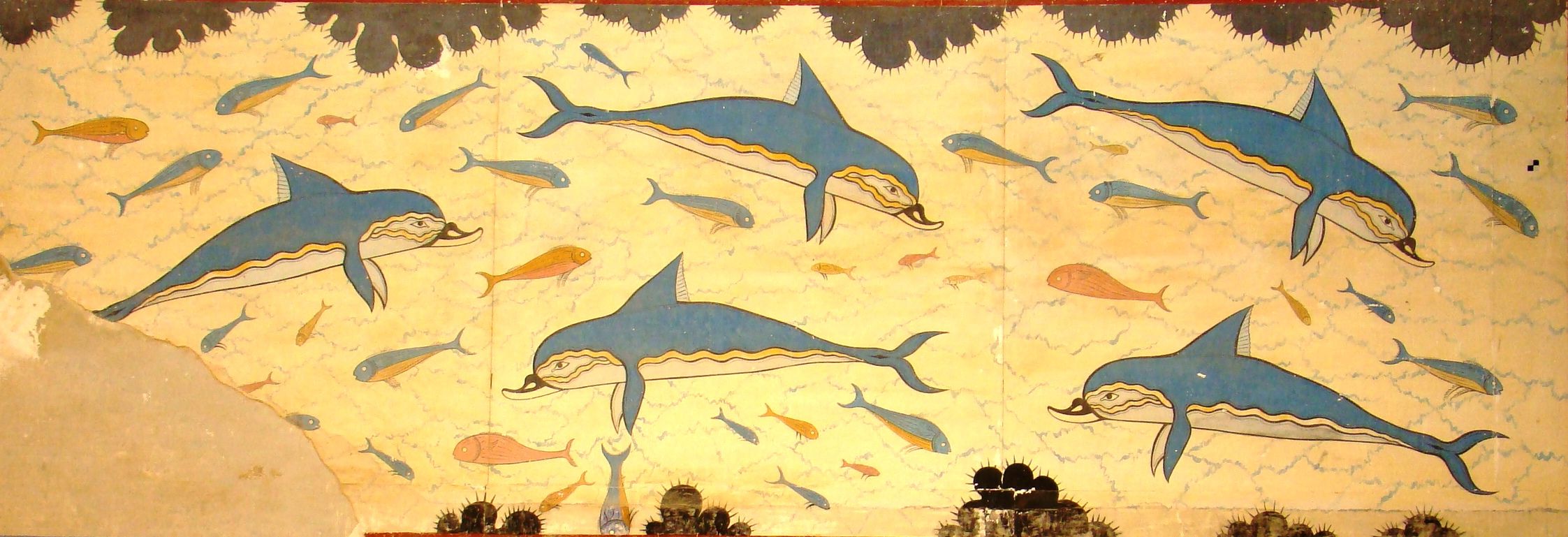

The impressive complex of buildings on the site wasn’t constructed all at one time, so there is no specific date associated with it. My impressions of its realism stemmed from an archeological gaffe made by Sir Arthur Evans, who first discovered the site and excavated it from 1900 to 1905 CE. His contribution was enormous, but he went a step further; he had parts of the palace “re-created.” Although his re-creation was based on archeological evidence, this was not an action archeologists were supposed to take. Primarily what he had done was the renewal of the paint and frescoes, but it was exactly this that made the site come alive for me. I found the playful dolphin frescoes in the queen’s boudoir so charming that I bought a small vase replica of one of the pieces found there with the same dolphin motif. It sits in my bedroom today. I walked through Knossos accompanied by this queen who loved dolphins as much as I.

The queen’s dolphins at Knossos, Crete.

The queen’s dolphins at Knossos, Crete.

I’ll write more about travel in Crete and the Minoans and their myths next week—But now to modern Crete.

I discovered a modern side to Crete’s myths and suffering when we came upon a most unusual contemporary sculpture by an isolated stretch of road in the Cretan mountains. This memorial was dedicated to more recent heroes—real ones. The sculpture consisted of a series of modernistic concrete figures with the names of the Cretan resistance fighters killed during the World War II German occupation engraved on them. The first two have fists upraised; the last three appear to be victims of torture or have been hung. It is a dramatic remembrance.

I know this was in an earlier blog, but take a closer look at these figures of Cretan World War II resistance fighters.

I know this was in an earlier blog, but take a closer look at these figures of Cretan World War II resistance fighters.

The Cretans are a people who have stridently reacted to the yokes put on them by other, initially more powerful, forces. In World War II, the Battle of Crete was fought by Germans, who were parachuted in near Chania, against British forces. While a technical loss for the Allies, the cruelty of the German troops united most Cretans in direct and indirect resistance to the Germans, requiring the German command to install many more troops on the island than first anticipated, thus depleting their troops elsewhere. The stories of Cretan bravery include both men and women, range from children to old people, involve priests, shepherds, storekeepers, housewives, and many others.