Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble is always nonviolent, goal oriented, grass-roots, and a critical USA mechanism for righting wrongs. For a young, black boy from the state of Alabama, the idea of getting into any kind of trouble was an anathema. His mother was adamant about that. She knew it was the only way to keep her son alive in the context of the Jim Crow South. But John Lewis (2/21/40 – 7/17/20) was intent on attending Troy State University (TSU), a state segregated school for whites, in his hometown. He had listened to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK, Jr.) on the radio and followed the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, and was impressed with Dr. King. So he wrote him and asked for his help in his legal battle to attend TSU. Dr. King not only wrote him back, but sent him a round-trip bus ticket to visit King in Montgomery. That was the beginning of Lewis’s activism, and King became his mentor, then, really, Lewis became his equal.

Not surprisingly, both his parents, Alabama sharecroppers, worried and, at first, discouraged his activism for fear of his being hurt and, worse, killed. It was just next door in Mississippi that 14-year-old Emmet Till had been kidnapped, tortured, murdered and his body thrown into the Tallahatchie River in 1955 for allegedly making an inappropriate remark to the white female store clerk, Carolyn Bryant. Gradually, his parents came around to support his activism, although, as parents, I imagine they still worried and held their breath many times. They had cause to be concerned. Lewis was arrested at least 40 times for his civil rights nonviolent (no crime) actions, most occurring between 1960 and 1966. He suffered numerous beatings by police, state troopers, and white mobs.

Following his parents’ wishes, Lewis gave up his idea of going to TSU and attended the American Baptist Theological Institute then Fisk University, both in Nashville, TN and historically Black colleges, receiving a B.A. in religion and philosophy. While a student there, he became involved in establishing the Nashville Student Movement and copied the Greensboro, NC lunch counter sit-ins at the segregated Woolworth lunch counter in Nashville, which led to his first beating and fractured skull at the hands of angry white protesters and arrest by local police. That was the Jim Crow South: the peaceful protestors were arrested and those who beat them were not only free, but encouraged.

March 7, 1965 is one of the most important dates in civil rights history. John Lewis and Hosea Williams, another MLK, Jr. activist, emphasized nonviolence and the ‘turning the other cheek’ form of Christianity to the approximately 600 demonstrators they led across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, AL to protest issues for voting rights for Blacks in the segregated South and, ironically, the unprovoked murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson by Alabama State Trooper James Bonard Fowler on February 18, 1965 during a civil rights protest in Marion, Alabama. That peaceful march was a protest against the arrest of James Orange, a field secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), working on voting rights for Blacks. Jackson, a former soldier, deacon in his church, and a civil rights activist was with his mother and grandfather at the march when it was attacked by Alabama State Troopers. The three of them fled into Mack’s Café, but were followed inside. As Jimmie [unarmed] tried to protect his mother and 82-year-old grandfather from being beaten, he was shot in the stomach and died 8 days later in the hospital of his wound. Fowler was not indicted until 2007 and held accountable for manslaughter to which he pleaded guilty and given 6 months in prison in 2010.

Jimmie Lee Jackson’s grave site, which I visited and paid my respects

Back to the Selma march; first with Lewis’s description of his experience: “You saw these men putting on their gas masks and behind the state troopers are a group of men, part of the sheriff’s posse, on horses. They came toward us, beating us with nightsticks, trampling us with horses, and releasing their tear gas. I was hit in the head by a state trooper with a nightstick. My legs went from under me. I don’t know how I made it back across the bridge but apparently a group just literally took me back.” — John Lewis recounting the Bloody Sunday confrontation of March 7, 1965, in Selma, Alabama, in an oral history interview conducted by the House historian, Dec. 11, 2014.

John Lewis on the ground being beaten by Alabama State Troopers; photo by Spider Martin, who deserves a post of his own, which I will do in the future.

While on the Edmund Pettus Bridge (named for a Ku Klux Klan leader) over the Alabama River, the protestors faced a large force of sheriff’s deputies, state troopers, and deputized possemen, some on horseback, who had been authorized by Alabama’s segregationist governor George Wallace to “take whatever means necessary” to prevent the march. Told to disperse, but given no time to do so, the law officers attacked. [An excellent example of the rule of law in the segregated South!] They were doused with tear gas, overrun by horses, and beaten with whips and billy clubs. As a result of the brutal assault, more than 50 marchers were hospitalized, including Lewis, whose skull was fractured…again. Before going to the hospital, he spoke to television reporters and requested President Lyndon B. Johnson to take action in Alabama. Television had come into its own by then and millions of American witnessed the, what quickly became known as, Bloody Sunday. Within 2 days, supportive demonstrations took place in over 80 American cities. There is no question but that this witnessing of what the reality of the segregated South really was like contributed to the passage 5 months later of the landmark Voting Rights Act, which was signed into law by President Johnson on August 6, 1965. But in 2013, Alabama sued for a critical part of that Act to be weakened; basically that the jurisdictions covered no longer needed federal approval to change their voting laws to be discriminatory. The result: a wave of new voting laws that dismantled protections for voting rights and disenfranchised voters in the affected states. It was the now infamous Roberts Court (as Roberts has discarded the Rule of Law concept and our Constitution and Bill of Rights) with Roberts joined by Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas, and Alito for the motion and dissent by Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan.

Edmund Pettus Bridge in recent times, which I walked across with tears in my eyes.

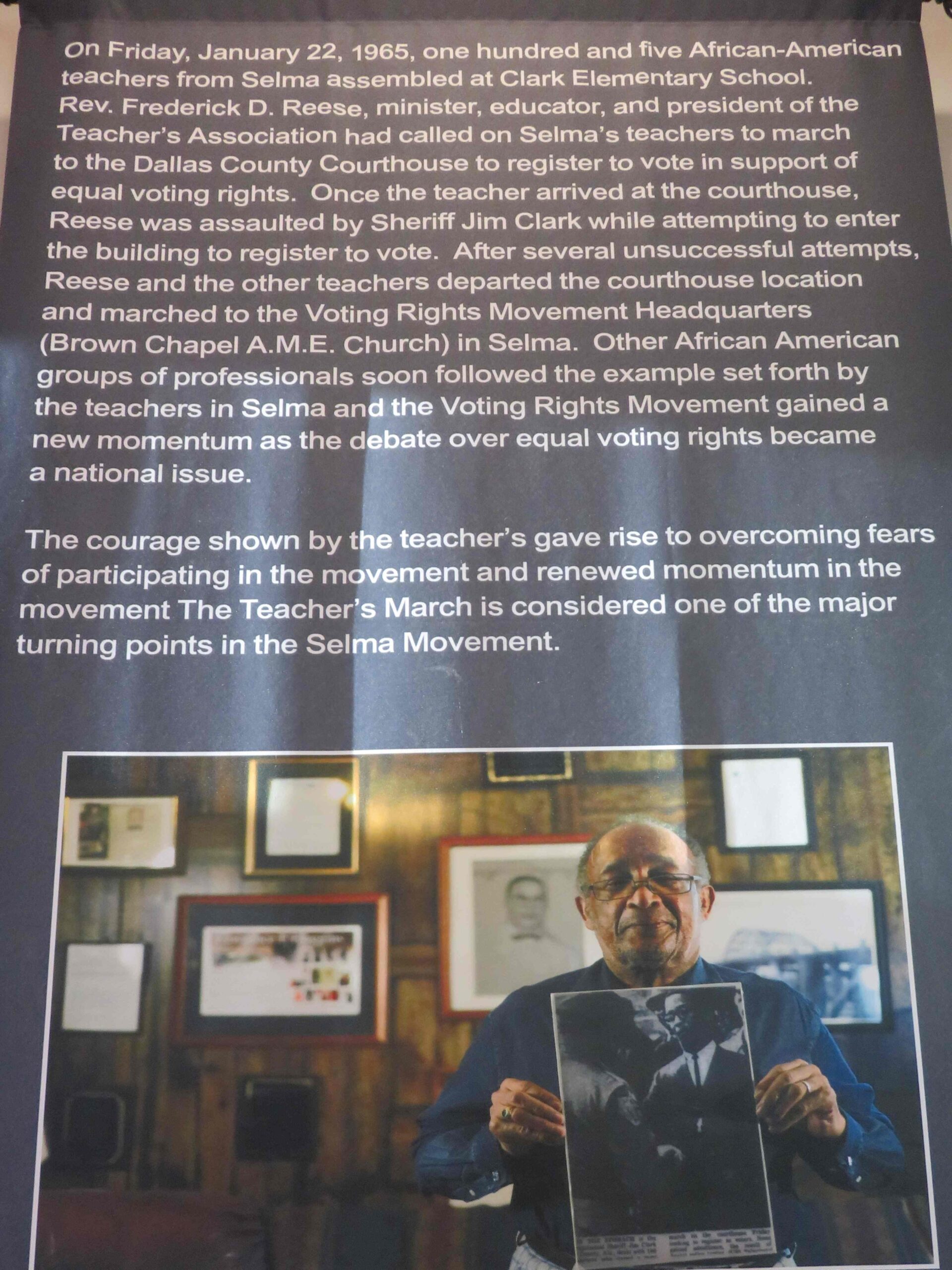

Even before Bloody Sunday, Blacks in Selma wanted the vote, as was their right. At the Selma main museum, I learned about how Black teachers organized to try to register to vote. Another peaceful protest for a Constitutional right met by violence from ‘law enforcement.’ Let’s NOT let this happen again!

[Unfortunately, today with the tech bros, AI, and other tools, television no longer necessarily shows reality. It is selectively doctored, even created to titillate, stimulate, agitate a specific point of view or captivate audiences so the sponsors can make more money. There are many tools for discerning what’s real, but who bothers? As long as it supports our point of view, we’re sold.]

The Library of Congress in December of 2019 opened an exhibit about Rosa Parks, about whom I’ve written in a previous post. John Lewis spoke at that event, saying, “Rosa Parks inspired us to get in trouble. And I’ve been getting in trouble ever since. She inspired us to find a way, to get in the way, to get in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble.” Because of his upbringing to not get into trouble, it was important for Lewis to emphasize this was Good trouble, Necessary trouble.

“Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month, or a year, it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.” – A tweet from Lewis in June 2018.

“Get in good trouble, necessary trouble, and help redeem the soul of America.” — Remarks by Lewis during the 55th anniversary of Bloody Sunday atop the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on March 8, 2020, shortly before his death.

“Find a way to get in trouble – good trouble, necsary trouble. Make our country what our country should be, and help change the world. You can do it.” Commencement address, May 16 , 2014, University of Maryland Eastern Shore.

John Lewis was an activist and a politician with integrity and a widespread mission for civil rights for all, e.g., LGBTQ+, for which he never gave up making Good Trouble, Necessary Trouble in his lifetime. He was known as “The Conscience of the Congress.”

To learn more about John Lewis, you might want to read his book, Walking With the Wind: A Memoir of a Movement or watch John Lewis: Good Trouble, an independent documentary film directed by Dawn Porter and distributed by Marigold Pictures, available on various streaming channels, and to rent for $3 or buy for $10 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iyl-GY1_sG0. “[It is] an intimate account of legendary U.S. Representative John Lewis’ life, legacy and more than 60 years of extraordinary activism – from the bold teenager on the front lines of the Civil Rights movement to the legislative powerhouse he was throughout his career. After Lewis petitioned Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to help integrate a segregated school in his hometown of Troy, Alabama, King sent ‘the boy from Troy’ a round-trip bus ticket to meet with him. From that meeting onward, Lewis became one of King’s closest allies. He organized Freedom Rides that left him bloodied or jailed, and stood at the front lines in the historic marches on Washington and Selma. He never lost the spirit of the ‘boy from Troy’ and called on his fellow Americans to get into ‘good trouble’ until his passing on July 17, 2020.”

An excellent summary of one of our real heroes. We should often be reminded of the need for good trouble and necessary trouble.