The theme of my blogs is travel, but special kinds of travel—read on. In my last blog on November 15 I looked back to an early traveler: Odysseus and the beginning of the Odyssey legend. Here’s the continuation of that ultimate travel story. It took Odysseus ten years to get home from Troy, just as we spent ten years, but our trip home took us around the world. Some of the text of this blog is from my book, Voice of a Voyage: Rediscovering the World During a Ten-year Circumnavigation. I have not included the endnotes that are in the book.

As I mentioned last week, I re-read The Odyssey as we traveled Odysseus’s “wine-dark seas.” I had a map of the island and had made notes from various sources, including The Odyssey itself, about the location of such places, particularly where, on his return disguised as a beggar by Athena, Odysseus met Eumaeus, his old swineherd. It was “by Raven’s Crag and the spring called Arethusa.” We had rented a car to explore, and after a drive up torturous mountain roads around multiple tight curves and between rows of olive trees branching overhead with black cloths spread below to catch the ripening crop, we arrived at a small, one-room museum with a curator—both the museum and the curator dedicated to the memory of Odysseus.

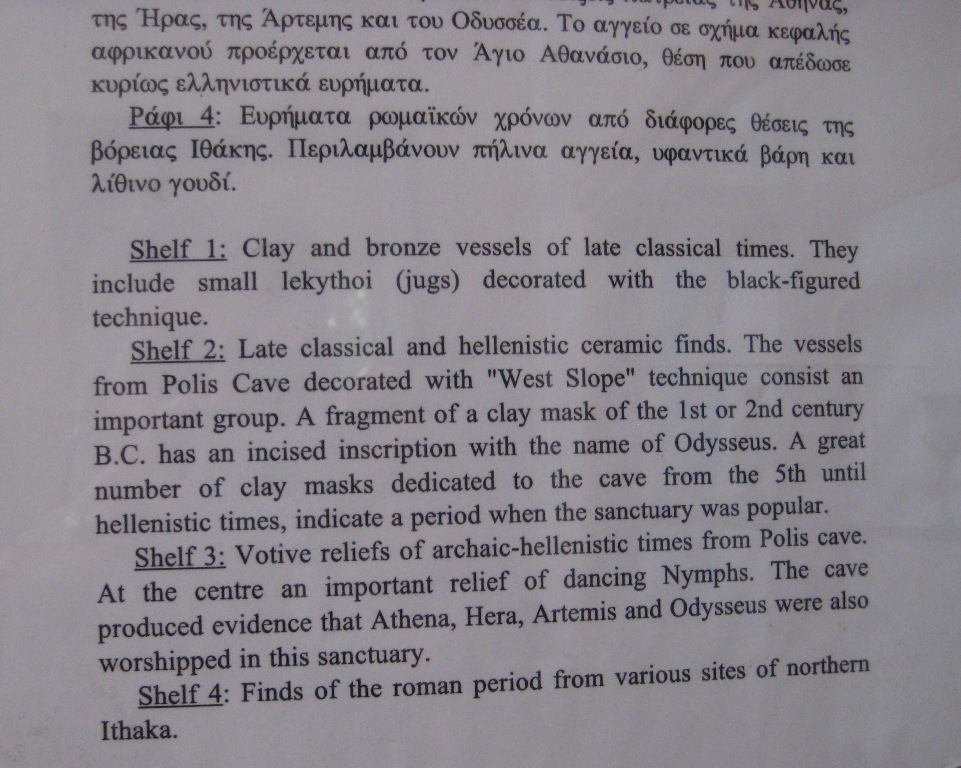

Sign in the tiny museum

An Italian archaeologist, the only other visitor to that well-hidden place, explained to us some of the finds there. Its prize possession to my eye was a piece of clay fragment with the distinct words in ancient Greek “Dedicated to Odysseus.” His palace was clearly near here. The curator gave us directions. The way was more like a wide goat trail than a road, so we parked and walked around, Wayne was impatient to be on, but I needed to feel this ground that belonged to Odysseus.

One of the shards related to Odysseus

The sky was clear, the sun bright; there were wild grasses, a few flowers—no doubt they could be considered weeds—and several boulders piled up at one end of a small open area that seemed like an old gravel pit. It was not an attractive place, and a small weathered, hand-painted, wooden sign was all that indicated it as the site of Odysseus’s home, and the sign didn’t seem as if it would last another year or two. Yet, he stood here, growing up under his father’s, Laertes, watchful eye and benign rule, becoming king himself, and finally returning after twenty years—ten in battle against Troy, ten on his odyssey to return to Penelope and Telemachus and his dearly beloved land. This is sacred land to the literature and tradition of Western civilization. I breathed in not just the sun-warmed, sea air of this Greek island, but time, age-old time. I closed my eyes and floated on Homer’s “wine-dark sea”; watched his “rosy-fingered dawn”; saw the young, “thoughtful Telemachus,” and Athena, too, always bright-eyed, eyes ablaze and flashing when settling on her favorite, “the nimble-witted, noble, much-enduring Odysseus.” In my mind’s eye, I also saw Penelope, no longer having to pluck out the stitches of the shroud she pretended to make for Laertes to keep the ravenous suitors at bay while Odysseus was away. They were all here.